Does anyone still care about privacy?

The Globe and Mail, a Canadian newspaper, ran an interesting piece titled “Surrendering to surveillance” that struck a chord with me. For a while I had been sharing a similar theory emphasized by the article; it doesn’t seem like many of those that I talk to (in a personal context) take privacy all that seriously. “Oh, they already know everything anyway” or “what are they possibly going to do with my data” are common refrains. The feeling is nuanced, it isn’t “I hate that it is this way and I wish I could change it”, more so apathy, a “who cares?”. I don’t want to be the proverbial old man yelling at the clouds, instead I want to really dig into why this might be, and what we might be able to do about it.

Do people value privacy as an overall goal?

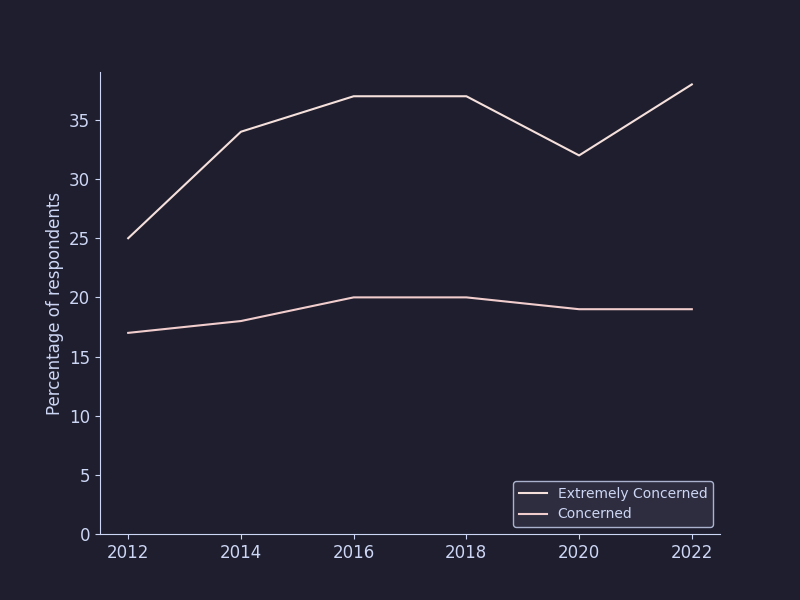

Some do, and the percentage of people that are in the top category of concern has increased since 2012. Consider a survey commissioned by the Office of the Privacy Commissioner in Canada which asked about overall concern about protection of privacy. This line chart shows those that have responded with “Extremely concerned” (7 on a 7 point scale scale) or “Concerned” (6 on the same scale) from 2012 to 2022[1].

Full data table

| Year | Extremely concerned (7) | Concerned (6) | Somewhat (3-5) | Not concerned (1-2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | 25% | 17% | 46% | 11% |

| 2014 | 34% | 18% | 38% | 9% |

| 2016 | 37% | 20% | 35% | 8% |

| 2018 | 37% | 20% | 35% | 8% |

| 2020 | 32% | 19% | 36% | 13% |

| 2022 | 38% | 19% | 36% | 7% |

Acknowledgement is the first step towards action, however in order to act on these concerns Canadians would also have to have a clear idea of tangible steps that they can take. Across three different questions in the same survey, this idea is explored. The conclusion; roughly half of Canadians responded that they were knowledgeable about privacy rights, knew how to protect their privacy rights, and felt confident in the privacy implications of new technologies[2]. 50% is either a good thing or a bad thing, depending on if you are a glass half full or glass half empty kind of person. The main point is that there are still a lot of people who are at a loss for what to do.

Below, I will outline 4 premises that paint a broad picture of how I’ve been thinking about privacy recently. These premises can be thought of as arguments, not necessarily facts, but as positions to consider.

Premise 1: As an individual, you cannot fully control your privacy online

While individuals have some control over which technology they use, in other cases they have little to no control at all. Consider tax filing or other government interactions. Citizens must present accurate information such as names, addresses, and identification numbers in order to pay taxes, receive a license to drive, or apply for jobs. Once data changes hands, there is nothing that the individual can do, trust must be placed in the individuals who now manage the data at scale.

This also extends to the private sector. In the 2024 Connected Consumer Survey, Deloitte, a consulting firm, finds that 61% of American consumers thought that technology companies would “[fail] to adequately protect my personal information”, and 56% believed that technology companies would “[use] my personal information in ways I didn’t authorize”.

From a technical standpoint, the only way to ensure that the company itself cannot read or access information while doing business with you would be end-to-end encryption. However, this isn’t possible in many use cases. Take dating apps for example, in order to show profiles and match users, the server needs to have access to the information. There isn’t going to be a dating app come to market that offers end-to-end encryption anytime soon[3]. Users want their data to be used for one purpose (finding a match) but not for other purposes, and no settings or techniques that the user applies will fully be able to mitigate the risk completely.

Premise 2: Privacy is inherently networked

If I communicate with someone over Signal, but they then go and post the messages on a website, my messages have been compromised even though I was using one of the best messenger apps around for security and privacy. If you are a member in a group, the security of that group depends on the least digitally secure individual in that group.

Additionally, all parties must agree on a method to communicate through. If I want to use SMS and you want to use WhatsApp, there is no compromise. Either we agree to use SMS, WhatsApp, or agree on a third platform to send the message through. This is one of the hardest things about moving towards a more secure and private world. Take the findings from the Canadian survey. If we assume that only those that are “Extremely Concerned” are interested in downloading an addition app to communicate through, and ignore any congregation of concerned people (so people’s preferences are randomly distributed), then the chance of an agreement to use the secure app is 0.38 x 0.38 = 0.144, or 14%. The nuclear option is to refuse to communicate with someone unless it is done through the secure app, however if the trade-off is losing connection with a parent or close friend, the value placed on privacy would have to be immense (or the value from communicating with those people very low).

This extends beyond just 1:1 messaging or group chats, and into networks in general. Instagram and Facebook are terrible for privacy, and yet, in order to be part of the network, users have to accept the conditions. The power of this network effect is immense as there are few drop-in alternatives. With messaging, using Signal is almost the same as SMS from a feature perspective, you send a message, you get a message. With Instagram, being able to have a place to add photos and videos and share them freely is more difficult[4].

Premise 3: Private services cannot be free for everyone

Many of the biggest names in tech have made their fortunes through a ubiquitous business model; users get a service for free, the company sells advertisements or sells data directly to make money. There isn’t any technical reason why a private service couldn’t add advertisements into their service, but it wouldn’t be targeted at all, and therefore would make much less money. Ads in print newspapers still exist, though few marketing departments have them as their number one choice.

Some private services, such as Tuta and Proton simply charge most users to compensate for the cost of running the service. Others, such as Signal, rely on some percentage of the users donating to cover the costs of an otherwise free app. The key point is that some users have to pay for what they could otherwise get completely for free, minus the privacy aspect. Once real money is on the table, the willingness to pay for privacy is measured, and for some people that is next to nothing. As difficult as it may be to accept, that is a valid judgement to make if it is made with the awareness that it is happening; I give you my data so that you can target ads towards me better, and in return, you give me an email service for free.

The problem arises when monopolies form due to the majority created by the users who willingly and unwillingly make this trade. If 95% of the population uses two similar email services, it gets harder and harder for standards to justify supporting interoperability with other services. In The Internet Con by Cory Doctorow, interoperability is emphasized as one of the key components to avoiding a complete takeover of the internet by Big Tech. It is the loss of this interoperability that stings the most, because it re-enforces network effects that push more people from the fence into the world of less private services.

Premise 4: The value placed on privacy changes over time

One of the most common sayings when talking about privacy is “I have nothing to hide”. When saying this, what people really mean is “I have nothing, given the current laws, enforcement and norms where I am, that justifies inconvenience”. Laws change all the time, and what may be considered okay to transmit one year may become illegal the next year. Crucially, what an individual deems “right” from a moral sense will seldom align perfectly with what is legal or illegal in a country. As a silly example to illustrate this point, I have no problem saying “I think that it would be a waste for Canada to send military assets to the moon”. However, maybe in 5 years, Canada passes a law that says that it is illegal to comment on how the military should operate. I might not have broken the law, because I commented before the law came into effect, but in that hypothetical future others may treat me differently due to shifts in norms. That statement is (hopefully) pretty safe, yet it is vital that people can express views without fear of oppression or punishment[5]. The greater the punishment, or the greater the gap between what people judge as right and what the law says, the higher the value placed on privacy.

Even when norms or laws don’t shift, there are still bits of information, particularly pertaining to health, that could easily be used to discriminate against individuals if they are not protected. A future employer or insurance company may not wish to do business with me if they know that I may make more claims than expected, or take a few extra sick days above the average.

Possible solutions

Views on privacy and its importance are always going to be disparate. While it would be lovely to write a single blog post that convinces everyone to be more privacy conscious, nobody is that convincing on any topic. Instead, there are some low hanging fruit that may begin to shift the needle.

Meet people at the margin, and try to move to the most private service that can be agreed to

If you are currently messaging someone through SMS, ask if they use any other apps to communicate. If they use WhatsApp, but don’t want to use Signal, switch to WhatsApp, it is more secure than SMS. Don’t let perfect be the enemy of good. We need to avoid shunning people for using services that aren’t the golden standard but are vastly better than less secure alternatives[6]. Wait for the next opportunity when they would consider using something else and then bring it up then.

Start with easy swaps

Of all the swaps to convince people to make, Signal is probably the easiest. There is nothing lost (the individual doesn’t have to give up any network), it is free, and the feature set is pretty comparable to what they would get in any other messenger. The username functionality is really cool and has broad appeal to even a non-technical audience.

For those services with a more entrenched network, your job doesn’t have to convince people to leave, rather, it can be to show people that a world outside of those services is possible. When a store asks for a review on Instagram, just calmly saying “ah, sorry, I don’t have an account” shows that it isn’t as dominant as they thought it may be. If you are nervous about leaving the platforms but ultimately wish to, that’s okay and expected, my advice would be to try a pause and see that it probably isn’t as bad as you think it will be.

Support entities focusing on privacy

While not everyone may want to switch to private services right now, it is vital that these services stay open as alternatives. Once monopolies become entrenched they can become different to shake. Standards get rewritten, support for universal protocols is diminished, and everyone loses out. Laws that support open standards and interoperability are great things to push for.

Privacy is one of those things that you often don’t realise is important until you need it to be.

Many survey executive summaries will use questions like these to make statements like “93% of Canadians care to some extent” about XYZ topic, which is a summation of all scores on the scale but the lowest. I disagree with presenting the results this way, as most people care somewhat about a lot of things. I care “somewhat” about whether garbage collection is every 7 days or every 8 days in my city, but I don’t really pay much attention to it. An issue would have to be particularly benign for me to respond with “I don’t care at all”. The full data is presented in the table if you wish to see the percentage for all scores. ↩︎

Figures 3, 4 and 5 of the report. ↩︎

The companies could offer end-to-end encryption on the messages, similar to how Facebook offers end-to-end encryption on the content of messages in messenger. ↩︎

There are alternatives emerging in the fediverse, however I wouldn’t consider them drop-in replacements. ↩︎

Within limits, freedom of expression/speech laws have never been absolute and never will be. Often this is referred to “protected speech”, which some comments can fall outside of. ↩︎

This is comparable to how some Linux users will make fun of those that use Linux Mint for not being Linux enough. ↩︎