Perfect recall

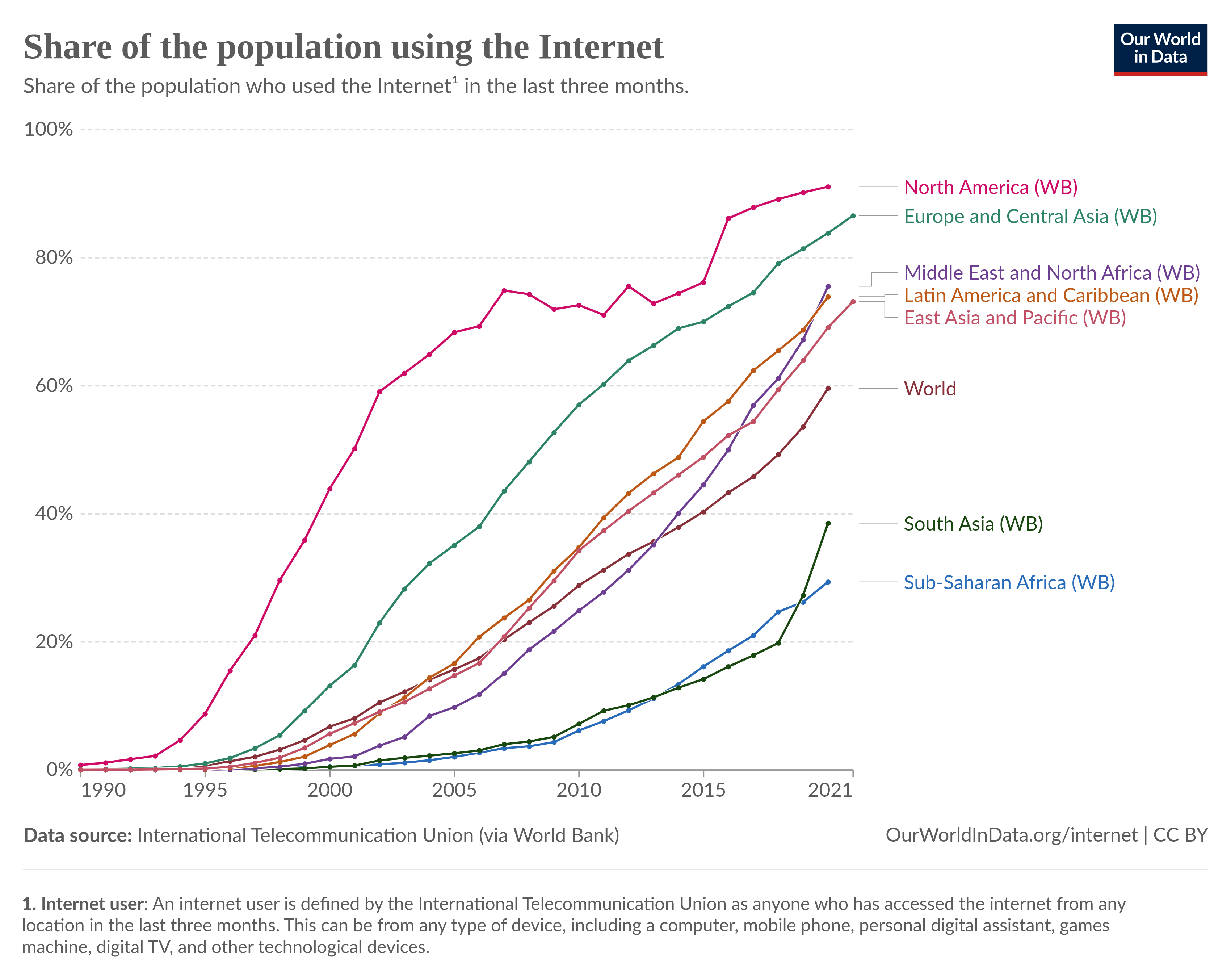

We consume and generate, a lot of information per day. With more people using the internet and generating data around the world, there will be even more communication: more emails sent, more articles written, and more data to store and recall. During the period 2011 through 2021, the percentage of individuals worldwide using the internet almost doubled, from 31.2% to 59.6% [1]. People are joining the interconnected infrastructure of the modern web at a blistering pace, and yet there are still billions more that remain unconnected. When they too join the global network, we can expect even more ideas to join the chorus.

Our problem now turns from producing data, to sorting data. With so many data being added to the pool, it may seem hopeless that we will ever be able to consume it all. Of the data that we do consume, we also must be able to find it again, in essence “remember” it. Humans have limitations when it comes to memory that can make the modern world feel incredibly challenging. While there have been some incredibly bold claims that the human brain can hold 108432 [2] bits of information, practically we all know the experience of not remembering what we had for dinner last week. Unremarkable things get lost in the shuffle, and many of the data points that we interact with each day, such as emails, texts, and various business documents, are in fact unremarkable.

Our problem now turns from producing data, to sorting data. With so many data being added to the pool, it may seem hopeless that we will ever be able to consume it all. Of the data that we do consume, we also must be able to find it again, in essence “remember” it. Humans have limitations when it comes to memory that can make the modern world feel incredibly challenging. While there have been some incredibly bold claims that the human brain can hold 108432 [2] bits of information, practically we all know the experience of not remembering what we had for dinner last week. Unremarkable things get lost in the shuffle, and many of the data points that we interact with each day, such as emails, texts, and various business documents, are in fact unremarkable.

One solution to this problem was the concept of a “second brain”, in which we externalize the knowledge that we gather into a networked system. This could be an app, such as Obisidian or Logseq, or a simple notebook in which we write down what we have learned for the day. This concept has exploded in popularity, so much so that Tiago Forte has written an entire book (and website) dedicated to the concept, aptly called “Building a Second Brain”. As a movement, it is known as “Personal Knowledge Management” or “PKM” and seeks to do away with some of the pesky limitations that the human brain has in the modern era, particularly when it comes to memory. I have used and written about my journeys with such software here, and overall I believe that while useful, we should not dedicate our lives to trying to externalize every piece of knowledge we consume.

Today, Microsoft announced a new feature called “Recall” coming to many Windows devices that really highlighted how deep the connection between humans and their devices has become, particularly on the topic of memory. Essentially, the computer will take a screenshot of whatever is displayed on the desktop on a continuous basis for on-device AI. The onboard “copilot” will seek to recognize things from those screenshots to help you surface them later. This requires 25GB of storage by default, but may involve more if the user selects to increase the frequency in which screenshots are taken. This may fundamentally change the way that many users navigate their computers. The youngest generation already does not understand the concept of computer file structures, and views search as the primary way to retrieve information from a vast unsorted pool. Now not only files will be searchable, but potentially anything that was on your screen at a particular point in time.

The technology’s strength is also its greatest pitfall. There are tons of sensitive applications displayed on screen that may be a bad idea to log in storage as saved images. Email inboxes, chat messages, and password managers are all things that should be safeguarded. Taking screenshots while these applications are open just means that you then need to make sure that the image library is as locked down as the application it took a screenshot of — which would be annoying if using the search tool was an incredibly regular operation. If we took away the AI features, would you feel comfortable if someone said “from today onwards, your computer is going to take an automatic screenshot every few seconds, and store it such that anyone logged in to your user can view all of them?”. Even with the option of excluding certain things from the tool, this still means that you would have to remember to add an entry into the settings every time you used a new application. This tool also affects others beyond those who consent to using it; if I am on a Zoom call with someone who is using this feature, my face is going to be picked up throughout the call and stored by the tool.

This is a different kind of “second brain”, one in which the computer mops up everything and throws it into a single bucket, with all trust placed with a single company. Suddenly the local login to a computer running this feature may become one of the most important secrets you store. Someone with access to the PC can not only see data that is stored normally, but also numerous snapshots which may contain data which has since been deleted. Codes which are displayed on screen once, such as API tokens between apps, may suddenly be stored in these images.

Note that Recall does not perform content moderation. It will not hide information such as passwords or financial account numbers. That data may be in snapshots that are stored on your device, especially when sites do not follow standard internet protocols like cloaking password entry - Microsoft Copilot Plus FAQs

In the age of AI, it would seem that even the choice of what is worth saving has been made for us (even if that brings serious security drawbacks). From the direction that tech companies are heading, it seems we should seek to have the AI help us remember everything, because our human brains cannot comprehend the deluge of data that we are now faced with. This is a nightmare for privacy, and this feature will almost certainly be opt-in by default on the new devices, with many users not fully grasping the implications that using the feature may entail.

With Windows 11 losing marketshare to Windows 10, it remains to be seen whether consumers will flock to this feature or away from it, and that will be the ultimate signal to Microsoft about whether features like this are okay or not.

“Data Page: Share of the population using the Internet”, part of the following publication: Hannah Ritchie, Edouard Mathieu, Max Roser and Esteban Ortiz-Ospina (2023) - “Internet”. Data adapted from World Bank. Retrieved from https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/share-of-individuals-using-the-internet [online resource] ↩︎

Wang, Y., Liu, D. & Wang, Y. Discovering the Capacity of Human Memory. Brain and Mind 4, 189–198 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1025405628479 ↩︎